J.T. McDaniel Official Site

Audio Books

January 2014 Interview

January 2014 Interview

with J.T. McDaniel

Yet another example of me interviewing myself. It’s about time, really, considering the last one was in 2006.

Interviewer: Nice outfit.

JTM: Thank you. It’s a picture. I’m not dressed like that just now and you know it.

Interviewer: True. Why were you dressed like that then?

JTM: It was the company’s holiday party that day. The theme for the day was to wear white. Being the sort of contrary old goat that I am, I decided that they didn’t really say how much, so I just wore black everything with a white tie. Sky Masterson does Christmas, if you like.

Interviewer: So what have you been up to since the last time you interviewed yourself?

JTM: That sub novel I was working on back in 2006 turned into a long short story, or maybe a short novella. In either case, it ended up being published as part of This and That, and I finally used the Eighteen Hours title I’d been playing with for most of a decade.

Interviewer: How’s that selling?

JTM: Someone buys a copy every now and then. I sell more Kindle books than printed ones these days.

Interviewer: Best sellers?

JTM: None that the New York Times would notice. Bacalao is a fairly steady mid-

Interviewer: You’re acting now?

JTM: I was always acting. There was a bit of dry spell there, but let’s be honest, radio is certainly a form of improvisational acting. Or it was back when I doing the DJ bit. Back when a DJ was still a DJ, and not some idiot making funny noises by fooling around with the turntable. My hero was always Doctor Johnny Fever, except I never did drugs. Bourbon, but never drugs.

Interviewer: What got you back into actual acting?

JTM: I had some problems with my voice a while back. Turned out I’d developed polyps on the vocal folds, which my ENT doctor cured using inhaled steroids. I had a few nervous days over that, because I have glaucoma, and when you have that you tend to avoid steroids like the plague. But the docs say that’s just the injected type, so from an inhaler is okay, and it cleared up the polyps.

Interviewer: And this got you started acting again?

JTM: Once the polyps were cleared up, I had to do voice therapy for a while. We were working on redeveloping my voice, both speaking and singing. It had tended towards the hoarse for quite a while. Anyway, when we were working on the singing part, my therapist mentioned there were tryouts for Into the Woods that evening in Delaware, and she thought I might want to consider trying out because I’d make a good Narrator. I did, and the director agreed with her, though I didn’t tell him she was the one who got to to try out until something over a year later. She got Cinderella in the same production. Great voice.

Interviewer: What about yours?

JTM: Used to be great. When I was in my 20s I could sing pretty much anything in the baritone repertoire, including opera, though I have a preference for Broadway. These days it’s more limited. Still pretty good, but nothing like it used to be, and I can’t sing nearly as high, either. I could never actually sing tenor parts, but I could get out a decent B-

Interviewer: Before they weren’t?

JTM: Back when I could have done them best, they hadn’t been written yet. The Phantom is out in any case, since the show is still running in the West End and on Broadway and hasn’t been released except for schools. Wilkinson threw that falsetto into Valjean, and ever since audiences expect it, so that’s out, too. Maybe a little annoying, since it wasn’t actually written that way. So if I want to do the Phantom, I’d need to get hired for Broadway, or maybe a touring company, and that’s not going to happen. It’s too high now anyway.

Interviewer: How did Into the Woods go?

Interviewer: How did Into the Woods go?

JTM: All in all, okay. I walked out on stage, said all the lines, sang the solo in the first act finale, and generally managed to avoid getting lost. The Narrator is a surprisingly difficult part, considering he really doesn’t have that many lines. The problem is a lot of them sound very much alike, and they’re just scattered here and there throughout the show, very often with not much in between. You spend a lot of time off stage. Or you should, anyway. There were times when I could have been off stage, or at least in a blacked out section of the stage, that I found myself standing in a spotlight instead. The whole section of the prologue where the Witch is telling the Baker and his Wife what they need to do to break the spell on his house comes to mind. For most of that my spot could have been off, but we just didn’t have enough time for tech so we never got those light cues worked out and I stayed lit for the whole scene.

Interviewer: You were hairier then.

JTM: I had more hair in the back. I wore it clubbed briefly, but then had to cut it for a part.

Interviewer: Which part?

JTM: Inspector Ruffing, in Don Nigro’s Ravenscroft. He was a proper Edwardian gentleman, and the long hair just wouldn’t have suited the part. I kept the beard and moustache. I really thought about dying it, and my hair, back to their original brown color, considering the guy is supposed to be about 40, but the director said go for distinguished. Personally, I just thought I looked old. It didn’t help that my leading lady and potential love interest in the show was played by a 16-

Interviewer: Other than the leading lady was too young, good part?

JTM: I didn’t say she was too young, just that it felt a little creepy knowing how old she actually was. She was damn good in the part. And, yes, I liked the Ruffing part. It was murder to learn, but a lot of fun once I finally got it all down. Ruffing has well over 500 lines in Ravenscroft, roughly 49% of the lines in the whole play. Most reviews I’ve seen of the show comment on that. One reviewer said the part had “more lines than some books of the Bible.” That’s true, by the way. He also has more lines than Hamlet, but Hamlet’s are generally longer, so the Dane does have more to say. Verse is easier to learn, of course.

Interviewer: What did the critics say?

JTM: Nothing, really. The only review I ever saw was from a food critic. He liked the actors, but didn’t care very much for the play. He suggested that the audience would be best served if they didn’t bother trying to follow the clues and figure out the murderer and just watched it for the comedy. He’s right, of course, because nearly all of the clues lead nowhere, and the solution to the footman’s death just wanders in out of left field right at the end of the play. It really is a comedy, not a murder mystery.

Interviewer: What happened next?

JTM: The same theater was doing To Kill a Mockingbird, so I decided to try out for that. This time I went ahead and shaved. There was just no way a beard would look right in that time period. I ended up getting type cast as the judge, which isn’t a bad part for an older actor. In terms of getting an audience into the theater it was extremely successful. I think there was only one performance that didn’t sell out. There were some problems, though.

Interviewer: Such as?

JTM: We had a hard time casting the black roles. You have three essential black parts in that show, Calpurnia, Reverend Sykes, and Tom Robinson. Then there are a number of black townspeople, particularly in the court scenes. We had the three primary parts and that was it. And it took quite a while to find all of them. If he was younger, our Rev. Sykes would have made a wonderful Tom Robinson, but you need an actor who at least looks like he’s in his middle twenties. We did eventually find someone.

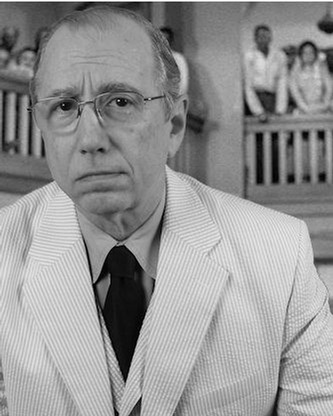

Interviewer: I’m thinking that’s not exactly a picture from your show.

Interviewer: I’m thinking that’s not exactly a picture from your show.

JTM: It’s a composite. I wore that seersucker suit, but with a bow tie. The background is obviously lifted from the movie. If you deconstructed the picture you’d find Gregory Peck hidden behind me. The glasses were different, too. Mine are a little too contemporary, so I switched to an old pair of gold rimmed reading glasses. I can’t actually read with them any more, but they fit the period better.

Interviewer: The black and white look works.

JTM: The black and white look was unintentional, though obviously I’d have had to use a different background if I’d kept the picture in color. But when I was taking the picture I didn’t have the magenta backlight you really need for green screen, so the green tint was bleeding into my hair. Removing the color also removes the greenish from the hair. Green screen sounds easy, especially after you see what they do with it in films, but it isn’t if you don’t have the sort of editing and compositing setups the movie producers can afford. Getting the green background lit evenly is actually the hardest part.

Interviewer: Do that much?

JTM: Some. The most popular video on my YouTube channel is me, dressed in Yugoslavian army surplus, doing a brief piece of the Ghost’s speech to Hamlet. That was done in front of a green screen in my living room. I adjusted the transparency of the foreground image (me) so that you could dimly see the background through it. The background was a still photo taken inside Hoover Dam. It looks appropriately spooky, anyway.

Interviewer: After To Kill a Mockingbird, what did you do next?

JTM: I auditioned for Man of La Mancha. That was with the same producer who did Into the Woods. I was offered Pedro, but ended up turning it down. I try to be at least somewhat honest with myself, and the truth is the only parts in that show I could do effectively would be Cervantes/Quixote or the Governor. That’s not me saying I need to be the lead, it’s me saying that those are the only two parts that are in my vocal range. Pedro’s a good part, but I don’t sing sustained high Gs any more. He should probably be younger, too.

Interviewer: After that you produced your own show. How did that happen?

JTM: In a roundabout sort of way. The original idea was that I would produce, and appear in, something that was going to be called Don Nigro’s Creatures. The idea was to take six of Nigro’s monologue plays, and one of his short one acts, and put them together as a complete evening. Two of the monologues and the one act featured my old friend Inspector Ruffing, and those were the ones I’d appear in. The show would have opened with Creatures Lurking in the Churchyard, which has a 36-

Interviewer: What happened to that idea?

JTM: I haven’t completely abandoned it. I’d still like to do it, really. At that time, no one had ever done Mermaid. For all I could tell you, maybe they still haven’t. The problem is that the six plays were parts of three different collections, and Samuel French licenses them by collection, not by play. We had progressed to the point where Don Nigro had okayed using Creatures as a collective title for the entire production, but it just turned out to be too much trouble to get the licensing straightened out. I could have confined myself to a single collection, but the major arc in the production was Ruffing getting older, and so we were back to three collections again.

Interviewer: Resolution?

JTM: I just gave it up. I had the theater booked for October, but there was still plenty of time to just cancel the whole thing, or put in a different show. All play licensing agencies will tell you the same thing, don’t book a theater until you have the rights. Good advice, but we were going to use The Abbey Theater in Dublin, Ohio, and when I came in to talk to them in April last year the earliest I could get three weekends was October. The place tends to be booked up way in advance. Of course, it’s also enough in demand that I could have simply canceled. They’d have had no problems filling those dates given a couple month’s notice. As it is, we had to clear everything out of the theater on Friday night and reset for the Saturday matinee, because there were shows booked for each Saturday morning of our run.

Interviewer: What did you do once you were sure you wouldn’t be doing what you’d planned?

JTM: I started looking for other shows. I ordered a bunch of perusal scripts for straight plays. Comedies, mostly. I didn’t want to try a musical right out of the gate, because rights are a lot higher, and you need musicians. Also, the Abbey doesn’t have an orchestra pit, so you’d have to put the musicians off to one side, or in the back corners of the stage behind teasers. There was also at least a possibility I’d have to hire union musicians in order to get the quality I’d insist on, and they’re not cheap. They also work by the week, so instead of doing three weekends, the only practical way to do the show would be to run it like a Broadway show, do six evenings and two matinees in a single calendar week, and then how do you find actors who can manage that schedule?

Interviewer: When did you decide to write your own show?

JTM: Somewhere in the middle of this. I’d written plays before, when I was much younger, and even still had one of them, a King Arthur story, on my bookshelf.

Interviewer: Did you consider doing that one?

JTM: Not for more than a few minutes. Honestly, it kind of sucked. There were some good scenes, but mostly it was pretty bad. It also had a huge cast. I think I was still in high school when I wrote it, and schools like to do plays with big casts, because it gets more kids involved. But this one had a big cast, and it wasn’t very good, so that was out. One of these days I may revisit the thing, maybe as a one act kids’ play. Just keep the parts that look like they’ll actually work and forget the rest. End it with Arthur holding the sword, maybe, and everyone realizing this kid is supposed to be the next king.

Interviewer: So then?

JTM: Then I started writing Coming Out. I wrote a complete play, and let a few people read it. The response was fairly consistent. “Interesting concept, but I don’t like any of these people.”

Interviewer: What was it like originally?

JTM: It had all the same characters, but several of them had different jobs. The original Bob Anderson was a Baptist minister, on the day of his retirement. It seems he’d stopped believing in God about ten years earlier, but kept preaching because he didn’t really know how to do anything else, and he didn’t have enough put aside to just retire. Now he did, so he was getting out. He was also coming out as an atheist, at least to his family. Younger son George arriving with his roommate/boyfriend causes Bob to spend a lot of time apologizing for a bunch of old sermons, where he’d taken a rather homophobic stance mostly because he recognized that fundamentalist Christians tend to be bigots and expect their preachers to support their neuroses.

Interviewer: What about Susan?

JTM: Susan was just a preacher’s wife. She’d figured out that her husband was an atheist, but never confronted him about it. She didn’t have as big part in the original version as she did in the final one.

Interviewer: And James?

JTM: He’s pretty much the same in both versions. A fundamentalist evangelist, probably really gay, so deep in the closet he’s even been successful at hiding it from himself, and with a very limited view of reality. If it isn’t in the Bible then it can’t be right. That sort of guy.

Interviewer: What about the pregnant secretary?

JTM: Oh, she’s there in the original. There she was the church secretary, but it wasn’t this long term affair you have in the final version. It was just a one-

Interviewer: How did the changes come about?

JTM: Reviewer comments from the people who’d read the original. There was general agreement that there was a story there, particularly the conflict between the preacher brother and the gay brother, but there was also a general agreement that only George seemed to have any redeeming qualities. An atheist minister just sounds like a con man to most people. Okay, con man is the basic job description of a minister, but most of them are able to con themselves as well, so at least they generally believe the supernatural nonsense they’re preaching. They don’t appear to just be in it for the money. Susan should have figured out her younger son was gay without having to be told. Well, she did, but it wasn’t clear enough. James just seemed evil, and he wasn’t even beating his wife in that version. His wife was his age, too, and had known him at least since high school.

Interviewer: What were the major changes?

JTM: The biggest change was that Bob became a college philosophy professor, and Susan became an English Literature professor. Bob was no longer coming out as an atheist; he’d been out for years, and wrote books on the subject. His father was an atheist as well, and a physics professor. Bob also became British, earned his doctorate at Oxford, and his father, who is still living and 97 years old, is a Lord with a title going back to George III’s reign. This makes his atheism more organic, which means the audience doesn’t think of him as a con man now. Some no doubt think he’s deluded, but that’s neither here nor there. Making him British, and the son of a peer, does add a bit of extra humor. There are several little jokes that simply wouldn’t work if he were American, mostly involving slang.

Interviewer: You played Bob, didn’t you?

JTM: Naturally. What’s the point of an actor writing a play if you don’t write a part for yourself? While I was learning it, I did find myself thinking it might have been a good idea if I’d written a part for myself that had fewer lines. Bob and Susan are at least technically the leads. They have the first lines in the show and the last, and the two of them are alone on stage at both ends of the show. The only real two character scenes are between Bob and Susan and Bob and Carol. Everything else is ensemble. Of course, if you’re looking for the stand out roles, the ones that you’d consider most likely to be nominated for acting awards, that would be James and Karen. As it happens, Jim LeVally, who played James, actually was nominated for an acting award for this show. That was on BroadwayWorld.com. The show was nominated for Best Original Play.

Interviewer: How’d that turn out?

JTM: Don’t really know yet. Voting ended on December 31, 2013, but now they have to validate the votes, which is likely to take a little while. When the voting ended the show had about 23% of the vote, which put it in second place behind a musical. What a musical was doing in the best play category I have no idea. Anyway, the musical had about 57% of the vote, so I presume they’ll win. Any changes in standings will probably be in categories where the vote is close, and eliminating a few duplicate or invalid votes would make a difference.

Interviewer: What’s it like producing your own play?

Interviewer: What’s it like producing your own play?

JTM: Annoying. We lost our co-

Interviewer: What did the audiences think?

JTM: What audiences? Honestly, we never had that many butts in the seats. In some cases, it may have been people who couldn’t find the theater. The Abbey Theater used to be easier to find before Dublin cut a section out of Post Road. Then, just before we opened, they started working on the part that remained, which cut off access except through Coffman Park. A friend told me that she and her husband spent something like 45 minutes driving around lost before they stopped at the Police Station and got directions. Another issue was publicity. The newspaper ignored it completely. Oh, they were happy enough to take our money for advertising, but despite having several months to do it, we never managed to get more than the usual four-

Interviewer: How controversial was it, really?

JTM: I suppose it depends on your point of view. A lot of people think the show’s favorable attitude toward same sex marriage is controversial. Others don’t care for having an evangelist as the bad guy. Perhaps because they find it hard to believe anyone could be as unfeeling or hardheaded as James. I’m not sure why. Most of his lines are just paraphrases of things you’d hear on religious television. Some of it isn’t even paraphrased. You can find plenty of TV preachers who think Hurricane Katrina was a deliberate, divinely imposed punishment for a New Orleans Pride parade. Or that New York was hit by Hurricane Sandy because same sex marriage was legalized. Hell, there were some very well known evangelicals who blamed 9/11 on gays, or on failure to punish gays. And American missionaries really did lobby the Ugandan government to pass anti-

Interviewer: You’re not gay, so why do you care?

JTM: Because it’s generally better to be right. As Bob says in the show, “If your moral guide tells you to do something your common sense tells you immoral, you bloody well don’t do it.” The biblical prohibition is so ambiguously worded as to be meaningless in any case. “…if a man also lie with mankind as he lieth with a woman…” What the hell is that supposed to mean? If we’re talking about missionary position sex, it’s impossible to violate that rule. Religious people are adamant that anal sex is forbidden, but that’s the only way a man could have sex with men and women in the same way. Well, oral, maybe, but they say you’re not allowed to that, either. So it’s a meaningless law, set down in a book that contains a huge amount of provable fiction and myth. The Genesis creation myths are patently ridiculous, though they probably seemed to make sense in a pre-

And marriage equality is hardly the only issue involved in this play. It certainly gives at least equal time to domestic abuse issues. Particularly where the abuse is religiously based, which it often is, hearkening back to the pseudo-

The major point of the play is just to let people be themselves, and don’t try to say that your personal prejudices are divine commandments. They aren’t. The ending, of course, is just comedy. It’s not a suggestion, and it’s not something I’d be likely to want to really do.

| Coming Out Website |

| 2001 Interview |

| 2005 Interview |

| May 2006 Interview |

| January 2014 Interview |

| Run Silent, Run Deep |

| Submarines at War |

| Harry Potter and the Cursed Child |

| Wahoo |

| The PaxAm Solution |

| Sea of Shadows |

| The Manor |

| Broadway Nights |

| Shrek, the Musical |

| The Phantom of the Opera |

| Love Never Dies |

| Returning - Sample No. 1 |

| Returning - Sample 2 |

| Returning - Sample 3 |

| Returning - Sample 4 |

| Returning - Sample 5 |

| Returning - Sample 6 |

| Characters & So Forth |

| Romiwero Interview |

| How a Submarine Dives |

| How a Persicope Works |

| Asdic, Sonar and Detection Gear |

| The Walter Turbine |

| The Typ XXVI Walter U-boat |

| The Revell 1:72 Scale Gato |